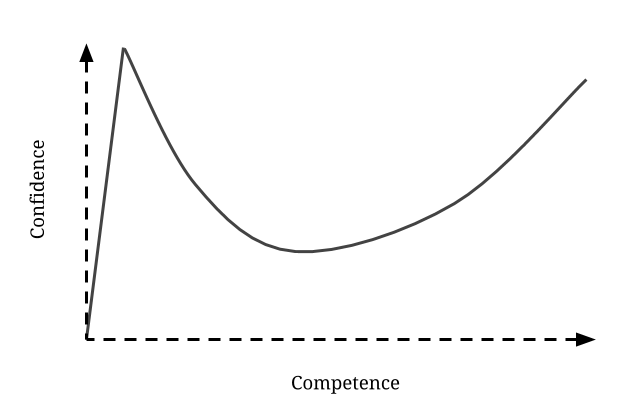

Why do ignorant folks tend to overestimate the extent of their knowledge? How do incompetent people often seem to be unaware of how deficient their expertise is? Turns out, we are not very good at evaluating ourselves accurately. And one of the most obvious manifestations of this psychological deficiency is the Dunning–Kruger effect, the cognitive bias of illusory superiority.

The realm of the “unknown unknowns”

In 1999, psychology researchers David Dunning and Justin Kruger published a study titled “Unskilled and Unaware of It: How Difficulties in Recognizing One’s Own Incompetence Lead to Inflated Self-Assessments” in which they described our tendency to to hold overly favorable views of our abilities.

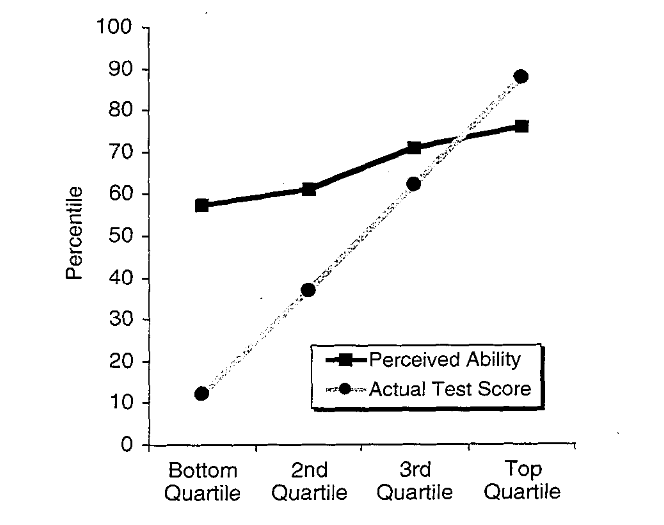

The researchers presented the participants with four tests assessing humour, logical reasoning, and grammar. Then, they asked participants to evaluate their own performance—how well or poorly they thought they did on the tests.

Not only did most participants overestimate their performance, but the least competent participants—the ones that scored in the bottom quarter—were more likely to overestimate their performance. The least they knew, the more they thought they knew.

But it doesn’t stop there. Dunning and Kruger wanted to better understand the source of this self-awareness and self-evaluation deficiency. Was it because they were genuinely struggling to distinguish between correct and incorrect answers, or was there something more going on?

In a variation of the original study, they first asked people how they performed on the tests, then showed them the test answers of other participants, and finally asked them to re-evaluate their own performance.

Poor performers struggled more than good performers to re-adjust their own performance based on the answers of other participants. In other words, not only do they lack the ability to measure their own performance, but they lack the ability to accurately measure performance in others.

Cognitive biases are wired into our system. Awareness is the best way to tackle these biases. Download a 40-page research report explaining the 10 most common cognitive biases in entrepreneurship.

DOWNLOAD REPORT“This meta-ignorance (or ignorance of ignorance) arises because lack of expertise and knowledge often hides in the realm of the “unknown unknowns” or is disguised by erroneous beliefs and background knowledge that only appear to be sufficient to conclude a right answer,” explains David Dunning.

From meta-ignorance to metacognition

The Dunning–Kruger effect sounds like a conundrum: if you don’t know what you don’t know, how can you know? Fortunately, there is a way out: it all boils down to developing metacognitive skills.

Metacognition means “thinking about thinking.” It’s an essential process to determine the best strategies for learning and problem-solving, as well as knowing when to apply them.

In their seminal paper, Dunning and Kruger write: “The central proposition in our argument is that incompetent individuals lack the metacognitive skills that enable them to tell how poorly they are performing, and as a result, they come to hold inflated views of their performance and ability.” And later: “Several lines of research are consistent with the notion thatincompetent individuals lack the metacognitive skills necessary for accurate self-assessment. Work on the nature of expertise, for instance, has revealed that novices possess poorer metacognitive skills than do experts.”

So how can you develop your metacognitive skills?

- Block time for self-reflection. Journaling has many science-based benefits. Beyond its many health benefits, it’s an incredible tool for metacognition. Whether as a weekly review or in another format, make sure to spend some time and to honestly evaluate your progress and your skills.

- Use second-level thinking to make decisions. Instead of jumping to the most obvious conclusion, use second-level thinking by asking yourself: what are some potential blind spots? What information am I missing? Disentangle the signal from the noise and use mental models to test your assumptions.

- Take smart notes. It’s much easier to notice gaps in our knowledge when we have a way to visualise our knowledge. That’s where taking notes comes handy. By building a note-taking habit, you will be able to identify thought patterns and mental shortcuts more easily. I personally use Roam for taking notes, but there are many alternatives you can use.

- Be aware of cognitive biases that may cloud your judgement. For instance, confirmation bias may reinforce the Dunning–Kruger effect by turning wishful thinking into actual beliefs. Learn about cognitive biases, and reflect on your own biases when you notice them.

Human beings are not great at self-evaluation. Being aware of this inherent limitation will make it less likely to fall pretty to the Dunning–Kruger effect. Block time for self-reflection, beware of cognitive biases, use second-level thinking, and take smart notes, and you will be ahead of the curve.