There’s only so much we can hold into our working memory—the system our brain uses to temporarily hold information while we manipulate it. The amount of working memory we use at any given moment is called the cognitive load. While both are theoretical concepts used in psychology and neuroscience, they have profound implications when it comes to thinking, learning, problem-solving, and decision-making.

Most people think we need to reduce our cognitive load as much as possible. But things are a bit more subtle than that. Certain types of cognitive loads can’t be altered, others are detrimental, and yet others are actually productive. Better thinking requires finding the delicate balance between all the different types of cognitive loads so you can make the most of your working memory.

The magical number seven

The classic paper The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information is one of the most cited ones in psychology. The author, George A. Miller of Harvard University’s Department of Psychology, may have been the first researcher to suggest our working memory capacity has inherent limits.

The paper is often used to argue that the number of objects an average human can hold in their working memory is 7 ± 2, which is known as Miller’s law. While Miller used the expression “magical number seven” only rhetorically, and the number of objects we can hold into our working memory is dynamic, later research has indeed confirmed our working memory is limited.

Our cognitive load is the main measure of how “full” our working memory is. When trying to learn something new or navigate your way through complex decision-making, it’s important to take into account and manage your cognitive load—or, more accurately, your cognitive loads.

Cognitive load theory

In the late 1980s, educational psychologist John Sweller developed cognitive load theory while studying problem solving in learners. He demonstrated that the learners’ cognitive load had an impact on their problem-solving performance. More recently, other researchers developed a way to measure perceived mental effort, which is thought to be indicative of cognitive load.

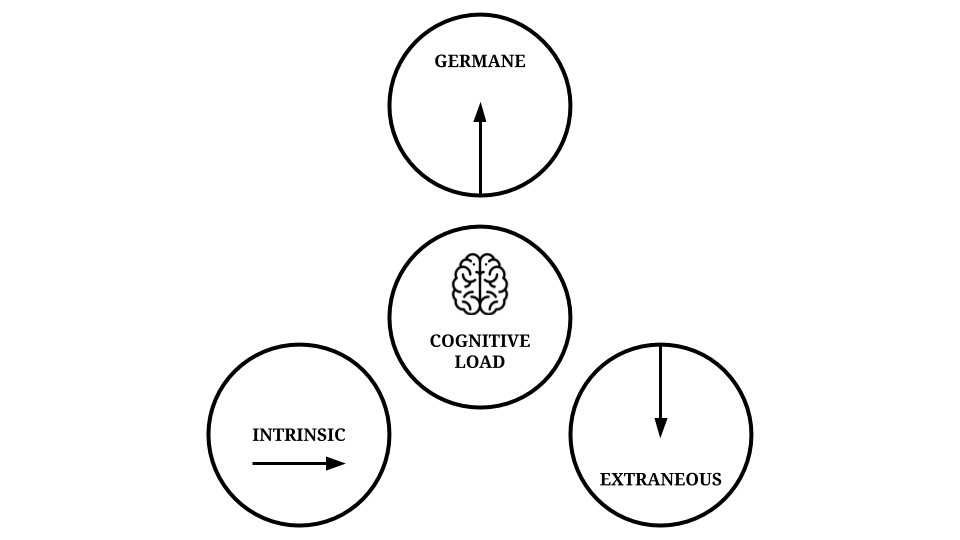

Balancing your mental effort is central to increasing your learning performance. To understand why, let’s have a look at the three types of cognitive loads:

- Intrinsic cognitive load. This is the inherent level of difficulty associated with a specific task. There is no way to alter the intrinsic cognitive load of a task. For instance, it will be easier to solve a simple calculation such as 3 + 3 compared to solving a differential equation.

- Extraneous cognitive load. This is the way the information or task is presented, and can be altered through instructional design. For instance, describing a concept visually or verbally will have an impact on how easy it is to understand.

- Germane cognitive load. This is the result of how the brain constructively handles information, which contributes to long-term learning. For instance, creating a concept map of a knowledge area will increase your germane cognitive load, which will help you understand and memorise better.

While the intrinsic cognitive load of a task is fixed, it is possible to play with its extraneous and germane cognitive loads. Specifically, in order to learn better, the way we study should strive to reduce our extraneous cognitive load (which is unnecessarily making it harder to think) and increase our germane cognitive load (which is helping us think better, even if it feels like more work).

Tools for productive cognitive load

Rather than just reduce your cognitive load, try to manage it. Many of these methods may feel like more work—it’s because they don’t reduce your overall cognitive load, but transfer the mental effort from extraneous to germane cognitive load instead.

- Chunking. Take individual pieces of information and group them into larger units. This method has been shown to improve the amount of information you can remember, as the chunks are able to be retrieved more easily due to their coherent familiarity.

- Thinking in maps. From mind maps to process maps and concept maps, thinking in maps is a great way to reduce the extraneous cognitive load of a task and increase its germane cognitive load by helping you form constructive associatiations.

- Brain dumping. A brain dump is a mind-clearing tool which helps take thoughts out of your mind and on paper, so you can better visualise them. It can be used as a precursor to creating a map.

- Writing. Many authors agree that writing is thinking. It’s been shown to help better understand content and improve your memory. To make the most of the generation effect, use the Feynman Technique.

- Collaborating. The title of this research paper says it all: A Cognitive Load Approach to Collaborative Learning: United Brains for Complex Tasks. Collaborative learning has been found to help improve learning performance, especially with high cognitive load tasks. Strategies include brainstorming solutions or creating a learning plan as a group.

If there’s one thing you should remember, it’s that not all cognitive load is detrimental to better thinking and learning. Some level of mental effort is required to understand complex topics and form long-term memories. With high intrinsic cognitive load tasks, productive cognitive load means ensuring that your working memory is put to good use by increasing your germane cognitive load and reducing your extraneous cognitive load.