Want to save this list of mental models for later? Subscribe to receive a PDF copy.

Remember how I told you that you need to build your own mental gym? Well, let’s talk about your mental equipment. Mental models are some of the most powerful mental tools at your disposal. They can help you think better, and faster.

“We all have mental models: the lens through which we see the world that drive our responses to everything we experience. Being aware of your mental models is key to being objective.”

Elizabeth Thornton, Writer.

But with great power comes great responsibility. Mental models are complex and rooted in human nature. They affect how we see problems, and how we see people. Depending on how you use them, mental models can be incredibly constructive, or destructive.

What are mental models?

Mental models are frameworks that give people a representation of how the world works. There are so many mental models that it would take a very long time to study them all in detail. Some are rooted in biological observations, others have been described in behavioural studies.

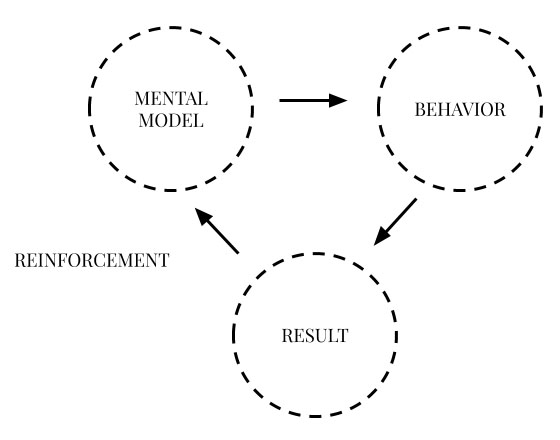

To put it simply, mental models are a set of beliefs and ideas that we consciously or unconsciously form based on our experiences. They guide our thoughts and behaviours and help us understand life. They’re basically thinking tools—shortcuts for reasoning.

For instance, knowing about network effects or about the law of diminishing returns helps you think about systems. Knowing about incentives or the availability heuristic helps you think about human relationships. Knowing about arbitrage and scarcity helps you think about markets and economic trends.

I have always been fascinated by mental models. The same way scientists are looking for a theory of everything, I sometimes wonder if there is a universal theory of the mind. An all-encompassing, coherent framework that would fully explain and link together all aspects of our biology and psychology.

While mental models are fundamental to understand how our mind works, they’re far from perfect. They need to be used in context, and often in combination. As many mental models are reflective of the complexities of human nature, some are also good to know about in order to avoid falling prey to them.

Think better with these 30 models

Here is a list of fundamental mental models that you can start studying and observing in your daily life right now, in alphabetical order. I may add more in the future, but 30 is plenty to get started.

- Anchoring: a cognitive bias where an individual relies too heavily on an initial piece of information—the “anchor”—when making decisions.

- Backward chaining: working backward from your goal.

- Classical conditioning: you’ve probably heard about Pavlov’s dog. Classical conditioning is a learning method in which a biologically potent stimulus—such as food—is paired with a previously neutral stimulus—let’s say a bell. The neutral stimulus comes to create a response (salivation) that is usually similar to the one created by the potent stimulus (in this case, food).

- Commitment and consistency bias: the desire to be and appear consistent with what we have already done.

- Common knowledge: knowledge that is known by everyone or nearly everyone, usually with reference to a particular community. Common knowledge doesn’t necessarily mean truth, but most people will accept it as valid.

- Comparative advantage: the ability to carry out a particular economic activity—such as making a specific product—more efficiently than another activity.

- Diversification: the process of allocating your resources in a way that reduces the exposure to any one particular risk.

- Economies of scale: the cost advantages that businesses obtain due to their scale of operation. The larger the scale, the smaller the cost per unit.

- Efficient-market hypothesis: a theory that states that prices fully reflect all available information. The hypothesis implies that is should be impossible to consistently beat the market, since market prices should only react to new information.

- Game theory: an umbrella term for the science of logical decision making in humans, animals, and computers.

- Hyperbolic discounting: a model which states that, given two similar rewards, people show a preference for one that arrives sooner rather than later.

- Illusion of control: the tendency for people to overestimate their ability to control events.

- Incentive: something that motivates or encourages someone to do something.

- Inversion principle: the process of looking at a problem backward. For example, instead of brainstorming forward ideas, imagine everything that could make your project go terribly wrong.

- Loss aversion: people’s tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. We are basically more upset about losing $10 than we are happy about finding $10.

- Margin of safety: in a business, how much sales level can fall before a company reaches its break-even point.

- The sailboat metaphor: a dynamic model of human needs devised by Scott Barry Kaufman, such as physiological needs, safety needs, love and belonging, esteem, and self-actualisation.

- Mechanical advantage: also called the law of the lever, it’s a measure of how much your strength is amplified by using a tool or mechanical device.

- Mere-exposure effect: a psychological phenomenon by which people tend to develop a preference for things merely because they are familiar with them.

- Norm of reciprocity: the expectation that we repay in kind what another has done for us.

- Normal distribution: a theory which states that averages of samples of observations of random variables become normally distributed when the number of observations is sufficiently large.

- Operant conditioning: a learning process where the strength of a behaviour is modified by reinforcement or punishment.

- Redundancy: the duplication of critical components of a system with the intention of increasing its reliability. For example, a backup or a fail-safe.

- Scarcity: the limited availability of a commodity, which may be in demand in the market. Basically, when something is in short supply.

- Signalling theory: the science of determining whether people with conflicting interests should be expected to provide honest signals rather than cheating.

- Status quo bias: a preference for the current state of affairs, where the current baseline is taken as a reference point, and any change from that baseline is perceived as a loss.

- Supply and demand: an economic model which postulates that, in a competitive market, the unit price for a particular good or service will vary until it settles at a point where the quantity demanded will equal the quantity supplied, resulting in an equilibrium for price and quantity transacted.

- Surfing: the business principle of “riding the wave” of a new technology, product, or trend.

- Survivorship bias: the logical error of concentrating on the people that made it past some selection process and overlooking those that did not, typically because of their lack of visibility. Happens a lot in entrepreneurship.

- Tribalism: a way of thinking in which people are loyal to their social group above all else.

How to use mental models

If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. A common misconception is that mental models should be dutifully practiced and applied in order to improve your mental performance. There are actually many mental models which you should work hard to avoid. For example, having an “illusion of control” can be particularly dangerous in some situations.

In order to grow as a human being, you need to be able to identify mental models, whether you are using them, or the person you are talking to is. Ideally, you need to make it a conscious choice to use them or not, instead of falling prey to the automatic thinking our brain loves so dearly.

“To break a mental model is harder than splitting the atom.”

Albert Einstein (but probably not)

So how can you challenge your mental models, identify them in others, and use them in a way that is actually effective and beneficial?

Here are a few tips you can apply to master mental models, rather than being enslaved by them.

- Be aware of your thinking by asking yourself provoking questions

- Gather information to challenge your thinking with actual facts

- Inquire into other people’s thinking and challenge their views

- Resist jumping to conclusions and suspend your assumptions

- Look for recurring thought patterns and unlearn them

A tool is only as good as its user. Only once you’re aware of your mental models, you can use them effectively to achieve your goals.

How to build your own mental models

In a fast-moving environment, mental models can be extremely useful to help you think fast and make decisions. After all, they’re great at giving you rules of thumb so you can, if done well, predict likely outcomes or behaviours.

- Observe people. One great way to develop your own mental models is to find inspiration in people. When you read a biography, ask yourself: why did they make this decision? What were they thinking? What mental model(s) did they use? It doesn’t have to be famous entrepreneurs or creatives. We all have a friend or a colleague whose work we admire. When you see them make a specific choice in a complex situation, ask them how they came to that decision.

- Take note of nature. Nature follows many rules that can apply to human decision making. For example, the tendency to minimise our energy output can be observed in many natural conditions, and incentives are a key drive in all creatures’ behaviour.

- Ask for feedback. Ask a friend or a colleague to observe how you act and to help you identify behaviours that may not be obvious to you. This can be an incredibly uncomfortable but mind-expanding exercise.

Don’t limit yourself to constructive mental models. You will observe mental models which you’d rather not reproduce. These are great to study as well, because it’s easier to avoid a thought pattern when you know how to spot it in yourself and others. Constructive or destructive, name your mental models and write them down.

5 great books about mental models

If you want to read more about mental models, here are some books to further explore the topic. Not only I found these books useful, but I’ve seen them recommended over and over again on Hacker News and other places.

- Thinking, Fast and Slow (Daniel Kahneman)

- Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion (Robert Cialdini)

- Metaphors We Live By (George Lakoff)

- Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions (Dan Ariely)

- The Art of Thinking Clearly (Rolf Dobelli)